From Candles to Charity – The Changing Nature of the Tallow Chandlers Company

In its 800 year history, the Tallow Chandlers Company has changed its function on several occasions. Initially a loosely allied street of craftsmen in the poorest slums of London, the Company has become an organisation focused on promoting education, charity and fellowship.

Here you can find out how this evolution took place and explore the ascending (and often descending) fortunes of the Company over the centuries.

As early as 1300, we can see evidence of tallow chandlers working together to support the candle making trade. This can be seen in the 1300 ‘Assize of Candles’ where Matthew le Chaundler ‘and his fellows’ were involved in setting the price of candles throughout the City.

The ‘Assize’ resulted in an altercation between the chandlers and a servant of the King’s Clerk, the latter of whom struck Matthew le Chaundler over a rise in candle prices. The servant was later fined several casks of wine for the crime and threatened with imprisonment if he should transgress against Matthew or any of his fellow candle makers again.

By the 15th century, the Company had gained the right to seize and destroy inferior goods associated with their trade. This right was later cemented in the Company’s first charter, which also enshrined their status as a livery company. This increased the power of the Company from an allied group of craftsmen to a body with a monopoly over the tallow trade in the City.

The right of search also provided a new source of income, as a portion of the fines made during searches were given to the Company.

Before the Reformation, many livery companies allied themselves with Catholic fraternities. The Tallow Chandlers Company was no exception to this trend, and its links to the Fraternity of John the Baptist can clearly be seen when considering the Company’s Grant of Arms.

Today, the Tallow Chandlers Company are one of just thirteen livery companies who retain their Medieval coat of arms and possess the oldest operative 15th-century grant of arms to survive to this day. The imagery of the Tallow Chandlers’ crest relates to its associated medieval fraternity and includes not one, but two severed heads of John the Baptist.

For more information on the heraldry and the Company’s coat of arms, see Our Company Coat of Arms.

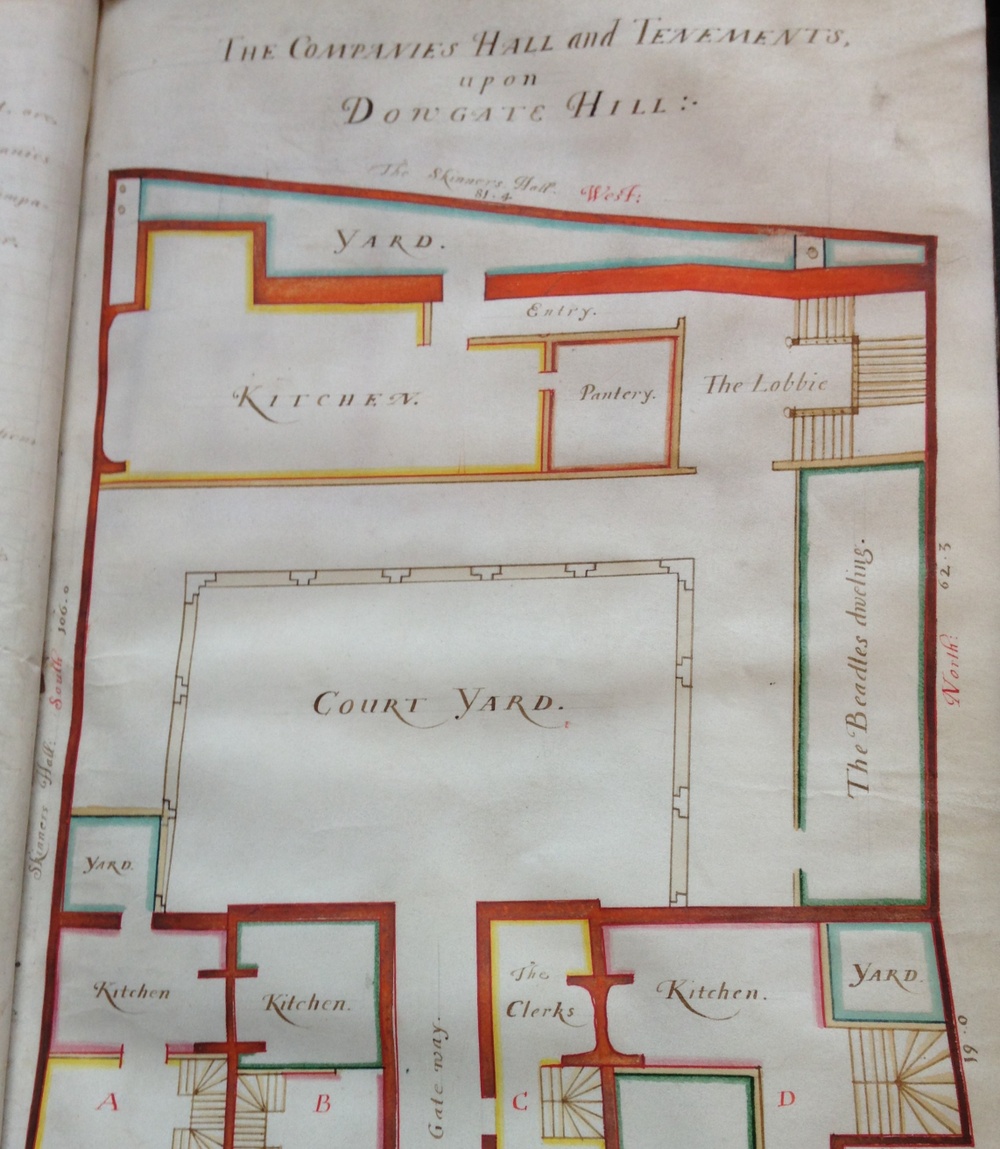

With the power of the liveries growing, many companies saw fit to purchase property to have a place for members to meet, dine, and discuss their trade interests. The site for the first Hall was purchased for £166 13s 4d in 1476. The deed for this site was recently rediscovered in a WWII ammunition case in the Company’s silver safe, where it was stored for safekeeping during the Blitz.

Little is known about how the original Hall looked, although there is a reference made in 1562 to there being a pair of stocks in the courtyard, presumably for punishing unruly apprentices!

Just a few streets away from Pudding Mill Lane, the original Tallow Chandlers’ Hall would have been one of the first livery halls claimed by the Great Fire of London. Indeed, by the second day of the conflagration, the Hall had been reduced to a smouldering ruin. Like many of London’s inhabitants, the liverymen worked quickly to save the Hall’s treasures, retrieving plate, gowns, and charters before looters and the flames could claim them. Many of the documents saved by the 17th-century Chandlers are still preserved by the Company today.

Despite the loss of their Hall, the 17th-century Chandlers continued to practice their trade and police the sale and quality of candle making in the City. The rebuilding process began in 1667 and the new Hall was completed in 1672. Part of the reason that the building was completed so quickly is due to the generosity and commitment of members, who donated considerable funds to the project. One member even made a gift of 50,000 bricks.

However, by the close of the 17th century, the Company was facing financial struggles and was overspending on wine, food, and entertainment. In 1695, the Beadle was prevented from handing out flowers at events, as the Company was £1400 in debt.

As we enter the 18th century, we can see the role of the Company changing significantly. A key factor in this change was the end of the Company’s involvement in searching for and destroying inferior candles. Searches had long been resented by craftsmen in the City, with various candle makers, such as John Ellars in 1692 being reprimanded for ‘great rudeness and misbehaviour towards the searchers.’

Events came to a head in 1709, where a disgruntled candle maker named Lewis Nicholls charged the Company’s searchers with destruction of property after they seized and broke candles in his shop in Piccadilly. Nicholls won his case, and less than a year later the Company suspended its searches.

While still relatively new, the Hall was already in disrepair by 1715, with infestations of Death Watch Beetles and vast quantities of filth rotting the walls near Cloak Lane being reported in the Company’s minutes.

A century later, the Hall was in such a state of disrepair that the panelling in several parts of the building had to be pulled down to remove inches of accumulated filth and dead pests that had built up in the walls. Throughout this period, the Company sunk into further financial difficulties, with membership in decline and the tallow candle trade becoming increasingly obsolete.

With the advent of electrical lighting in the 20th century, the Company’s priorities had shifted from trade to the management of its properties. There were just 84 members in 1931, with an average turn out to livery dinners being around 30.

However, the Company continued to survive during this time, despite considerable difficulties. Tallow Chandler’s Hall was one of just a handful of livery halls not to be completely obliterated during the Blitz and hosted several companies who weren’t so lucky during this time.

Despite their resilience, the Company was forced to face the reality of its financial situation after World War II. While the considerable work of the Clerk ensured that the Company received reparations for war damage, in 1958 a former Master requested to have his name removed from the court list, so as not be associated with a Company that was ‘financially in a hopeless condition.’

Fortunes improved in the following year, with the sale of Company property, and the Company began to re-establish trade connections. Throughout the rest of the 20th century, the Company experienced an influx in membership, with many new members coming from the organisations it had extended links to. The Company also began to increase its charitable activities, with a renewed focus on education.

.png)